- Home

- Claire Willett

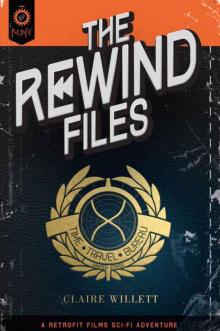

The Rewind Files

The Rewind Files Read online

The Rewind Files

A Novel

Claire Willett

Contents

Copyright

First Fleet

We want to hear from you!

Dedication

Quote

The Rewind Files Part I

1. The Repairmen

2. Look Past the Eggs

3. Just A Glitch

4. Election Day

5. Called To the Principal’s Office

6. How to Stop a War That Already Happened

7. Lie As Little As Possible

The Rewind Files Part II

Quote

8. We’d Like to Know a Little Bit About You For Our Files

9. Hello Darkness, My Old Friend

10. I Said Be Careful, His Bow Tie Is Really a Camera

11. If I Could, I Surely Would

12. The Mother and Child Reunion Is Only a Moment Away

13. I Got the Paranoia Blues

14. I Don’t Know Where I’m Going, But I’m On My Way

15. Everything Put Together Sooner or Later Falls Apart

BONUS MATERIAL: PART 2.5 of THE REWIND FILES

The Rewind Files Part III

Quote

16. Ghost Town

17. Bailey’s Crossroads

18. Boughs of Holly

19. Omelettes, Among Other Things

20. Last of the Time Agents

21. Saturn

22. Mars

23. Three Minutes

24. Remembering Where You’ve Never Been

25. Double Incongruity

26. The Loudest Noise In the World

27. That Ever I Was Born to Set It Right

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Recommended Reading & Viewing

About the Author

About Retrofit Films

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Copyright © 2015 by Claire Willett

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the author, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

Published by Retrofit Films & Publishing

5455 Wilshire Blvd Suite 1406

Los Angeles, CA 90036

www.retrofitpublishing.com

ISBN: 978-0-9861157-5-2

First Fleet

Check out First Fleet by Stephen Case -

a serialized ebook exclusively on Amazon.com

On the front lines of a war light years from Earth, where technology enables the continuous regeneration of soldiers, something unimaginably evil is brought back to life.

When a military space fleet accidentally revives an ancient alien race, they send out a single terrifying transmission for help before disappearing without a trace…

Now, a young scientist must race to find the fleet and save her only sister from an unknown fate.

Part 1 is Free!

We want to hear from you!

Let us know what you think!

Please leave reviews for The Rewind Files on Amazon!

Your feedback helps us make better books

Email typos or other notes to: [email protected]

To Christopher, who believed in this book before it was a book.

To my grandmother Lydia, our family’s original Watergate junkie.

To Dad, for everything.

“There is nothing more deceptive than an obvious fact.”

― ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE, The Boscombe Valley Mystery

The Rewind Files Part I

Manual Override Recommended

One

The Repairmen

Washington, DC. August 2112

Time travel sounds much more glamorous than it really is.

On paper, I’m Regina Bellows, a member of the elite, highly-trained team of history and technology specialists known formally as Government-Authorized Time-Slip Field Agents (Historical Realignment Division).

We call ourselves the Repairmen. (I just go by Reggie.)

So here’s what happened. About 80 years ago, there was an event we call the Great Rift – that’s when Li Chidong and Martina Garcia Lopez finally solved the time travel equation for transit of solid bodies and Lopez performed the first successful Chrono-Splicing to send herself back to 1995. Chrono-Splicing means you create a tiny rip in one small section of the General Timeline and insert yourself into it, temporarily merging it with your own permanent timeline.

Eventually it would allow us to create maps with agents’ GC (Garcia-Chidong) Map Coordinates.

I don’t want to bore you with all the math, but basically it meant that with the right equipment, anyone could send anyone anywhere.

The result? A giant goddamn mess.

And so began a massive global free-for-all as every government on earth dived headfirst into an epic international shoving match with one goal: To be first in line to send some bow-tied college professor back to whatever point in their own national history they felt like rewriting.

The Germans, being particularly motivated (and who can blame them), bribed their way to the front of the line and sent their first field agent back to 1907 to arrange for a fully-funded scholarship to the Vienna School of Fine Arts for a modestly-talented eighteen-year-old painter named Adolf Hitler.

It worked – Hitler’s totalitarian career was over before it even started, though at the cost of some truly ghastly paintings – but it knocked over the first domino. The entire 20th century began to unravel.

See, the U.N., NATO, all the great global policing agencies were founded during and after the Second World War. No war, no United Nations. No United Nations, no peace agreement in any country the U.N. ever brokered.

So Germany redeemed its reputation at the expense of genocide in Bosnia. Meanwhile, the American government took a clumsy swing at erasing slavery and ended up almost singlehandedly destroying the economy of the Western hemisphere for three hundred years.

Enter government regulation. The U.N. sent representatives from every delegate country to form a committee on global policing of time travel. An uneasy truce was declared.

No one nation was permitted sole provenance over its own country’s history, and they all agreed to leave the General Timeline alone. After that, for the most part the governments left time travel to the experts – meaning, us.

That’s where the Repairmen come in. We’re the ones sent in to clean up the mess and restore the General Timeline. After the practices and restrictions of time travel were codified, every member nation set up an official government-supervised bureau with registered agents trained both in system science and history.

Over the years we learned, through trial and error (sometimes fatal), how best to gently nudge history back on track when it slides off the rails, with minimal interference. You learn the rules on Day One at the Academy, so we’ve all had this drilled into our heads for years.

But it’s not necessarily common knowledge for civilians, so let me just very quickly run you through the basics.

The General Timeline (that means the real course of history the way it’s supposed to play out) does its best to self-correct when things go wrong. But it’s a big, slow, lumbering animal, and its attempts at repair can be cumbersome and sometimes insanely overcomplicated. Letting it correct itself is like performing a heart transplant with industrial logging equipment. Using an agent allows you to be accurate and surgically precise. Quick and clean. Get in, make the fix, get out.

Have you ever wondered

what it would be like to go forward in time and see

what your world will be like in fifty years, or go backwards to talk your past self out of

marrying that loser? Well, too bad. You can’t.

One of the first things you learn in agent training is that your own permanent timeline (meaning your natural birth to natural death) is off-limits. That timeline is locked until you die. You can go back and tackle Lee Harvey Oswald on the floor of the Texas Schoolbook Depository to keep him from shooting John F. Kennedy, but you cannot stop yourself from attempting ballet in the seventh grade all-school talent show.

Being in two places at once creates what’s called a Double Incongruity, and it can be deadly. A Chronomaly (that’s basically any incident that occurs which is not part of the General Timeline) can be very minor, or it can be significant enough that we send an agent in to repair it.

But an Incongruity is full of peril. It’s a Chronomaly on a scale so massive that it doesn’t just affect the way history plays out.

It risks affecting time itself.

It makes the Slipstream around you terribly unstable. Agents have died trying to transport out of an Incongruity. So whatever narcissistic fantasies you might have had about hopping around to watch the Greatest Hits of your own life play out in real time, just ask yourself if reliving that three-pointer from half-court in the junior varsity basketball playoffs is worth total organ failure.

Death is death. Even time travelers can’t circumvent it. Your real death, I mean. You can’t prevent it and you can’t undo it. Sure, if you’re trampled by an elephant while trying to patch the General Timeline around Alexander the Great, the tech monitoring your vitals will spot it, sound the alarm, and send somebody back to your initial transport site to pull you out before the elephant gets too close.

That’s because that rampaging elephant wasn’t really how you were supposed to die. In its own way, it’s a Chronomaly. Which means it can be repaired. But if you die in your own timeline, that’s it. You’re gone.

* * *

We learned all of this through trial and error, of course. Everybody wanted to believe that the possibility of time travel was somehow a magical ticket to immortality.

But the thing people don’t really understand about time is how fragile it is. We still have continuous aftershocks from that first era of disastrous intervention; you’ll think you plugged a hole but bits and pieces of chaos slide through.

So we do a lot of tedious, low-level patching. Napoleon leaves for battle and forgets his sword at home, so you have to sneak one into his scabbard before he realizes it. Abraham Lincoln cancels his theater tickets at the last minute because Mary Todd has a headache. Things like that.

Little dumb human things, all the tiny, meaningless moments that make up a life, only they aren’t meaningless because these people have no idea how important they will turn out to be.

And of course, you can’t tell them. “Abe, you have to go see the play tonight so you can get shot by an out-of-work actor.” That’s not how it works.

“The first rule of patching,” a professor said to one of my first-year classes, “is this: ‘For God’s sake, don’t make it worse.’” To that end, every field agent is equipped with a monitor for their Holistic Interference Output (HIO) Levels; that’s the tool we use to measure how much our presence and actions are impacting the General Timeline.

You have to keep it as low as possible. Dress in flawlessly period-appropriate clothing and walk through a busy, crowded public place like a town square or subway station? Good job, your HIO meter is ticking peacefully at a 1 or a 2. Your mission is a success and your patch will probably stick.

Land a plane in the middle of a Wild West shootout? That thing is blinking red and shrieking twelve different alarms in your ear, and your ass is getting so fired the second you step off that transport platform.

Anyway, I know this is all a little inside-baseball and the general public doesn’t really know or care that much about all of this. In fact, a lot of new Academy recruits don’t know or care that much about it either.

They come waltzing in with stars in their eyes, dreaming naïve little dreams about getting to hang out with Dorothy Parker and Oscar Wilde, and then they’re cruelly disappointed to learn that their glamorous fantasy career is like, 90% paperwork. That’s why only about ten percent of the new recruits actually stick around to get hired.

Me, I’m different. In the world of the U.S. Time Travel Bureau, my parents are like, mega-famous, so I grew up with this stuff. I could read an HIO meter by the age of five. There was no way the daughter of the legendary Carstairs and Bellows was not going to be among that ten percent of her class.

I didn’t exactly have a better plan — nor, to be quite frank — any plan for my life after graduation. So I figured I’d let my mom pull her strings to land me a boring desk job where I could sit in front of a computer screen all day until I figured out what I actually wanted to do.

Sounds okay, right?

Not so much, if you’ve heard of Watergate. Have you heard of Watergate? Of course you have.

That’s because I screwed up.

Two

Look Past the Eggs

It was 2:30 a.m. Four hours and sixteen minutes since my last break. Yawning, I stretched and tried to work out the kinks in my back from sitting hunched over the screen all day.

My eyes started to blur, and my whole body was experiencing that feeling you get from intense and prolonged lack of sleep, where you’re sort of hungry and sort of cold and sort of nauseous and every muscle in your body feels either too tense or too relaxed.

But it would be over tomorrow. Director Gray was coming for the report at noon. Once it was submitted, we could all go home, with an extra half day to our weekend. I just had to survive nine and a half more hours without screwing up.

There were twelve of us who had studied Mid-20th and been assigned to this floor. They discovered early on that the best way to keep track of agents in the field was to have a permanent data technician assigned to each one, continually monitoring any unusual activity in the General Timeline around the agent’s location.

I worked for an agent named Harold Grove, the senior agent on our floor whose field covered most of the latter half of the 20th century, alongside a tech named Calliope, an impossibly-gorgeous young woman with springy golden curls who looked like she didn’t have two brain cells to rub together, but was actually one of the smartest people I knew.

At the moment, Grove was in the field on a fairly routine mission to mend a troublesome patch on the 1968 Presidential election. According to the General Timeline — that is, the way unaltered history is supposed to play out — President Johnson announces that he won’t run for reelection, leading to a melee of Democratic candidates splitting the votes eight ways to Sunday and giving Republican Richard Nixon a clear run at the field.

Johnson’s health is failing and he’ll die just a few days after Nixon’s first term ends. Half a century ago, after the Great Rift, a group of well-meaning but clueless historians convinced themselves that a second Johnson term would have put an end to the Vietnam War, so they went back posing as campaign consultants and pushed him to run for re-election.

Well, no matter how many attempts they made, the system self-corrected; he was beaten in the primary, or he died of a heart attack on the campaign trail, or his wife threatened to leave him if he didn’t quit.

Once, he was hit and killed by his own campaign bus crossing the street. Something would always intercede to keep him from getting anywhere close to reelected.

Finally, growing desperate, the historians had Johnson’s Vice President, Hubert Humphrey (who was supposed to end up winning the nomination) assassinated and spread rumors that the Republican Party was to blame.

It worked. Johnson was reelected in a landslide of sympathy votes, and the entire system began to collapse in on itself in a staggering net of self-corrections that didn’t stop until another agent went bac

k in time and shot our own guys before they shot Humphrey.

Don’t worry, the agents didn’t mind. There’s a certain cachet among some of them about Rewinds — otherwise known as Emergency Manual Re-Edits. That’s when you’re killed in a flexible timeline you’re visiting and another agent gets sent back to retrieve you before your mission starts. It creates a lot of residual interference, though there’s no long-term impact on the agent.

Also, some of the more chest-thumping guys at the Bureau like to brag about it as a measure of how many risky missions they’ve taken. Myself, I prefer to take it as a measure of stupidity, and how many times a colleague had to put their own work on hold to go back and pull your ass out of the fire. It’s this attitude that made me very unpopular at school.

Three weeks ago, Grove spotted a news headline in the archives saying “JOHNSON ANNOUNCES RE-ELECTION BID” and immediately packed his bags to go fix the decaying patch.

While Grove was in the field monitoring President Johnson, Calliope and I were monitoring Grove. Or, she was anyway. I was trying my damndest to finish Grove’s field report in time to present it to the Director. And I was stumped.

Like I said, I’m the math girl on my floor. Grove usually hates his apprentices, and he really didn’t want to be the agent who got stuck with Katie Bellows’ daughter (“The last time you stuck me with a nepotism case I had to go back twice to Rewind that scrawny Ambassador’s kid out of the same air raid,” I overheard him snapping at the Director on my first day).

The Rewind Files

The Rewind Files