- Home

- Claire Willett

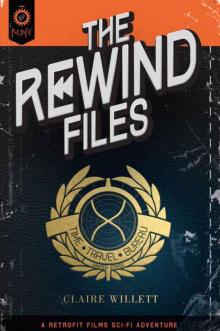

The Rewind Files Page 9

The Rewind Files Read online

Page 9

First Chongquing, and its fourteen million citizens. Gone in a flash.

Reagan sent a message to the Chinese government telling them to surrender. They ignored him.

Shanghai went next – population, eleven million. All dead.

Reagan was sure that would be the end of it. Instead, another handful of Chinese bombs peppered the Midwest crop centers, setting fire to thousands of acres of industrial wheat fields and decimating the country’s food supply.

Next stop, then, Beijing. 9 million citizens and the seat of government for the People’s Republic of China.

Once this city, too, had been turned to nothing but smoke and dust and piles of bones, it seemed both sides had had enough. Russia had begun the war as a stalwart ally of China, but had promptly switched sides after the destruction of Beijing, as had the rest of the Chinese allies.

With no friends left, no government, and 34 million citizens dead, China agreed to a cease-fire and was annexed by the United States. Many people more idealistic than me credited President Reagan’s sixteen years in office — his firm hand in military dealings, his forceful leadership as Commander-in-Chief — with the revitalization of the American economy in the 1990’s and the resurgence of the U.S. as the world’s dominant superpower.

* * *

That might be true. But all I could think, as I stared out at that massive, shadowy crater where the Washington Monument used to be, was about those 22 million Americans and 34 million Chinese.

All dead. And for what?

I walked around the circumference of the crater until I reached the front, where a twenty-foot-long bronze relief embedded in the cement below my feet showed a map of the old National Mall. I sat down on the ground next to it and watched the sun come up over the water, idly tracing the outline of the Old Smithsonian with my fingertip and thinking.

If the war was really a Chronomaly — if it really was never supposed to happen — then that meant 56 million innocent people were counting on me to find out what had gone wrong and stop it. 56 million people, killed in their offices and schools and homes and streets. Two nations’ histories turned into piles of rubble, from the Library of Congress to Beijing’s Forbidden City.

And me, a twenty-five-year-old computer tech who hates people, expected to fix it.

You know, no pressure or anything.

I sat there staring into the yawning dark chasm as the misty early morning light hardened into bright sharp sun, crisp and clear, with a snap in the air and a blue expanse of cloudless sky. The kind of day meant for a long country drive, or baking an apple pie.

Obviously it’s not like I’d be doing either of those things if I was staying — I would be sitting at a desk staring at a screen all day and then coming home to sprawl on the couch with a beer and no pants — but something about knowing that I was being forcibly ejected from my real life gave a little glow of nostalgia to everything I saw.

Finally I stood, dusted off my pants, and slowly made my way back home. Just window dressing around a math problem, I whispered to myself as I walked. You can do this.

I only had time to brush my teeth, pee, and run a decidedly half-assed comb through my hair before the knock came. I opened the door and was unpleasantly surprised to find — instead of Calliope with an enormous vat of coffee to tide me over on the drive — my mother instead.

Or, more accurately, my mother’s uniformed chauffeur Moulson, who shot me an apologetic glance as he stepped inside, wordlessly picked up my suitcases, and motioned me towards the elevator.

“I thought I might escape this hellish morning without a parental lecture,” I muttered as he pushed the button marked “LOBBY” and we descended. He chuckled.

“Well, that was pretty optimistic of you.”

“Shut up.”

“You Bellows women, you’re all a real treat in the mornings.”

He stashed my suitcases in the capacious trunk of the big, sleek black car parked outside my building and opened the door for me to slide into the roomy backseat next to my mother.

“I wanted a word with you in private before we left,” she said. “To the office, Moulson, please.”

“And a good morning to you too,” I said. She ignored me and went on as if I hadn’t spoken.

“Field work requires a specialized set of skills that take years and years to develop,” she said. “You lack many of those skills. You’ve always hated field work and you only have the barest minimum of experience needed to competently perform as a tech.”

“Your support means the world to me, Mom. I sincerely hope you know that.”

“But what you do have,” she went on, sailing blithely right past me again, “is instinct. I could send another agent on twenty drops in the same timeline with reams of research data memorized and she’d still miss something you wouldn’t. Your problem is that you don’t trust your instincts because you’d rather have the data. And in this situation, that could be fatal.”

“This is just the worst pep talk.”

“You’ve been prepped on all the facts and figures, so I won’t bother drilling you on any of that. I’m fully confident in your grasp of all the relevant material. But I have one piece of advice for you that you won’t have found in your files or heard in your mission briefing. This is the most important thing I can possibly teach you.”

This got my attention, and I briefly paused making exasperated faces at her and turned to listen. Once she saw that she had me, she nodded and pressed on.

“Field work forces you to make decisions quickly,” she said, “and then stand by and watch the consequences of those decisions play out in real time. It is not theoretical. You do not have the luxury of crafting a perfect solution to each problem. Situations will be thrown at you and you will be forced to adjust as they come. And the most crucial thing for you to remember, the thing that is most likely to get you through it unscathed, is this: lie as little as possible.”

“That’s good advice, I think Moses said that.”

“This is not a joke, Regina,” she said, and there was a steely urgency in her voice that shut me up. “I don’t think you have any idea what you’re up against here. Do you know what field work is? Talking to people. All day. Every day. Interacting with them. Trying to get information from them without ever looking like you’re trying to get information. You don’t get a file. You make your own data, and then you analyze it.”

“You will be asked questions you can’t answer. You’ll be in situations you haven’t prepped for. You’ll have to improvise. You will panic. And your brain will say, ‘Quick, make something up.’ But this isn’t a three-hour, teacher-supervised field drop for your Academy exams. You’re embedded. You live with these people.” She paused and looked at me seriously, to make sure I was listening.

“That means if someone asks a question, you don’t just have to give a plausible answer; you have to give a plausible answer and remember it every time. Say you make a contact who might have helpful information. Say you meet him in a bar, and he offers to buy you a drink. He asks what you’d like, and your logic brain clicks into gear and begins sifting through the lengthy list of period-appropriate cocktails you memorized, and you decide that a Republican junior secretary in 1972 would drink a martini, so that’s what you order. So all the while, as he’s getting to know you, he’s building ‘martini drinker’ into his mental picture of you along with everything else you say. Where you’re from. What you like to read. What church you went to on Christmas as a child. And the next time you see him, he’ll order you a martini.”

She continued. “And if you run into him at a cocktail party at someone’s house and the hostess is pouring he’ll tell her, ‘Regina would like a martini.’ Now it’s built into his sense of your identity. Except for one thing — you hate vermouth. But now it’s out there, you’ve said you like martinis, so every time he puts one in front of you you’ll have to pretend you like it.”

Her eyes were more steely than usual. Her voice matched

. “And not just barely manage to choke it down without grimacing, but enjoy it like a real martini drinker, enjoy it with flair in the way that someone who really loves gin martinis would do. It has to look real at every moment. And if even one time you slip up, it’s over, because then that becomes embedded into his mental picture of you — that you lied about a stupid small thing, that you kept on lying and lying about it — and then he’ll wonder what else you might have lied about, and the foundation of trust you’ll have painstakingly built will collapse entirely, and he’ll be worthless as a source. Whereas, if you had just ordered a glass of wine, none of that would have ever happened.”

I was silent for the rest of the drive, brooding over this. She didn’t speak anymore either. After a few minutes she pulled her tablet out and I could hear her tap-tap-tapping away as I stared out the window, watching the streets slip away behind us.

We pulled up to the Bureau several minutes later. Moulson pulled the car around to the back VIP entrance where my mother entered — I, a mere peon, was forced to line up at the front door security station every morning with the rest of the rabble, but department directors and up could pull their chauffeured cars into a secured private entrance with a password-protected elevator for their use only.

This was a safety measure; anyone coming in the office either had to brave the main lobby, with its endlessly invasive full-body examinations and retinal scans for unaccredited visitors, or have access to a director’s password.

I’m a cynic, so any time the Bureau installs another pointlessly expensive security tool as part of their ongoing waste-of-taxpayer-money contract with United Enterprises, my first step is always to annoy my mother by explaining to her how it can be hacked. The elevator had just gone in three months ago and this was the first time I’d seen how it worked.

“What if I had a contact in Human Resources with access to the security database that holds the list of passwords?” I said as Moulson piled my suitcases inside.

“We each choose our own password, they’re not shared with anyone, and there is no list. Transport Lab, please, Moulson, floor seven. They don’t live on any server. The elevator itself is the computer.” I had to admit this was pretty cool.

“What if I worked for United Enterprises and programmed the initial passwords into the elevator in the first place?”

“We change our passwords every fourteen days.”

“What if I came in with you once legitimately, like for a meeting or something, and then tried to sneak back later on my own?”

“The visual recognition software would catch you. If you weren’t a Bureau employee whose vitals were stored in the personnel database, it just wouldn’t open the doors.”

“What if I set off an explosive to blow the doors open?”

“Metal walls as thick as an old-time bank vault would slam down all around the lobby and you’d be trapped until security arrived.”

“What if I held a gun to your head?” I said.

“I’d rather you didn’t.”

“No, I mean what if I held a gun to your head and made you put in your password to let me in?”

“We each have two passwords for that exact reason,” she said. “One takes me to my floor and opens the door. The other takes me to my floor and opens the door, where we’ll find an entire squadron of armed guards waiting for us.”

“All right,” I admitted grudgingly. “Not bad.”

“I’ll be sure to pass along your compliments to the rep from U.E.”

“Although it’s a lot of high security for a building that just has a bunch of desks and computers in it,” I said. I was deliberately being a pain in the ass but she didn’t take the bait.

“It has nothing to do with our security,” she said, “and everything to do with appearances and profit. You don’t want to know how many taxpayer dollars went into purchasing this shiny metal box just so the Director can make the Committee feel important.”

“It’s all connected, do you see?” she went on, and I suddenly had the sense that she was trying to tell me something important that she didn’t have the words for. “If we had lost Grove — if you hadn’t caught the Chronomaly when you did — if the Director couldn’t bring presidents and prime ministers in for a tour to show off his shiny high-class technology — if things keep going wrong…”

“What things?” I asked. She shook her head.

“I don’t even know. I just have a sense. Something feels off. But that’s why all this matters, you see. We’re constantly battling for our own legitimacy. Snagging a fat corporate contract helps, flashy technology helps, lobbying politicians helps. But underneath all of that is the real, unglamorous, person-to-person work that gets things done.”

She glanced at me. “You believe in computers more than you believe in people, Regina, and that’s your fatal flaw. You believe that history is that big, lit-up screen in the server room with the endlessly scrolling lines moving up and down, points of light flashing on and off any time agents enter or leave the field.”

She shook her head. “But that’s not history. History isn’t made by that lit-up screen, it’s just recorded there. It is still now, as it has always been, made by people. And despite their complexities and contradictions, in the long run people are a far safer bet.”

I looked at her for a long time, still standing outside the elevator, arms folded. We were alone — Moulson had long since driven away — and in the hush of that small elevator lobby I felt a sudden primitive jolt of fear. Not the ordinary, sensible fear of screwing up an important job that had been plaguing me ever since I got this assignment less than a week ago, but a bigger, darker fear of something I couldn’t quite name.

I looked at my mother and tried to see her as a stranger might — thick dark hair pulled back to perfectly accentuate the whisper of gray at her temples, jaw set, a flawlessly-tailored gray suit on a body that had lost the taut angles and hard surfaces of her athletic youth after having two children but had lost none of its power and strength.

She looked like what she was – a member of the governmental ruling class with whom one did not screw around.

But suddenly, just for a second, I saw a flash of a different Katie Bellows inside her eyes, a worried parent whose face was drawn and tired. Then it was gone, as quickly as it came, and as we stepped inside the elevator she was so brisk and no-nonsense I thought I’d imagined it.

She placed her hand on a sleek metal panel, and a screen above it cycled through the database of Bureau employees until it found a match.

“PASSWORD RESET REQUIRED,” said the blinking red letters over the picture of her face onscreen, and she sighed, exasperated. “This is the most annoying part,” she said. “Exactly five characters, letters and numbers, no spaces, at least one special symbol every time, never the same combination twice.”

I don’t know what it was about this morning, this weird fear that something terrible might happen and I might never see her again, that was making me behave like an obnoxious teenager, but I couldn’t stop myself. Before she could stop me, I leaned into the keypad and typed, lightning fast, then hit the button marked “CONFIRM.”

She gave me the look. “Are you kidding me?” I giggled like a twelve-year-old. “Are you kidding me with this, Regina? You’re going to make me type that in twice a day for two weeks?”

“So you’ll remember me when I’m gone,” I said.

She sighed. “This was a terrible idea.”

“I told you! I told you that! It’s not too late to change your mind and not send me.”

“You’re going, Regina.”

I wasn’t sure when I would next get an opportunity to heave a childishly dramatic and exasperated sigh at my mother, so I was careful to make this one count. She arched one flawless eyebrow at me but said nothing.

It’s funny how things hit you; there was a part of me that didn’t fully and completely digest the fact that this was really, truly, actually happening until that elevator door whooshed noi

selessly open (God, even the elevator door noises were fancier in Mom’s wing of the building) and I saw the Director solemnly waiting for me. As an aide with a cart collected my bags and zoomed away with them, he and my mother shepherded me with an almost funereal ceremonial formality down the hall to the transport bay. I swallowed hard and fought the urge to run.

I’m not a politician, I wanted to say, I’m not a military general, I’m a twenty-five-year-old with a good math brain and a famous mother, where the hell do you get off sending me to save millions of lives when all I wanted to do today was sit at my desk and stare at numbers? I can’t do this. I can’t do this.

I must have whispered it out loud — or she could see it on my face — because as we entered the bay and I looked around that the gleaming whiteness of it I took a sharp breath, and suddenly, in a very un-Katie-Bellows-like gesture, my mother reached down and squeezed my hand.

My suitcases were piled on the transport platform already. Mark was there with a garment bag and pulled me into the changing room to put on my traveling outfit.

I stood there mechanically and let him dress me like I was a doll. All I was doing was trying to keep breathing, to keep from having a panic attack. He smiled at me warmly and patted my cheek. “You’re gonna be fine, kiddo,” he whispered. “You’re Katie Bellows’ daughter.”

“God, don’t remind me,” I whispered back, and he laughed. Mrs. Graham was there when we stepped out of the changing room, to put the final touches on my makeup and hair, and give me a few last-minute etiquette and deportment reminders that I immediately forgot.

Calliope held out a large burgundy leather handbag.

“Don’t let this out of your sight,” she said. “There’s a pocket sewn into the lining with a handheld in it. All your mission briefing files are there, for reference, and it’s wired for two-way communication so you can ring in if you need me.”

I nodded. She could tell — I’m sure everyone could — that I was starting to freak out a little bit, so she stepped onto the platform and gave me a reassuring hug.

The Rewind Files

The Rewind Files